This is a transcript of my podcast episode number 2. If you would prefer to listen to it, it is available on Anchor, Spotify, Apple Podcasts and YouTube.

Yesterday I was at a wellness retreat for the day, and the instructor that was leading it started with their introductions. You know when you talk a bit about health and safety, where the toilets are, basics like that? And they said that they use a body first approach, and I’d never heard of this before.

A body first approach is where you honour your needs. They’re the priority and they come first.

Honour your needs.

So it’s just simple things like if you need the toilet, you go to the toilet. She said, “don’t wait for me to finish talking. Don’t wait until it seems to be a convenient time to go to the toilet. If you need the toilet, you’ve got to honour your body and honour your needs and go to the toilet when you need it. Same with if you need a sip of water, don’t wait until it’s the break time. Have a sip of water whenever you want. Same with snacks.” And this made a big difference to me because I do have hypoglycaemia, so I get low blood sugars and it just meant that every now and then I got my snack out of my bag (it was just some nuts and raisins) and I was just munching on them. And usually I feel awkward, I feel rude, but I actually needed it because I was getting brain fog and I was losing my concentration. So I know I needed just a little pick me up then and I could have my snack knowing this.

Knowing that the instructor was happy for me to do that, and also that she had addressed that with the group, so there was no one going to be thinking of me: “That’s rude. Why is she eating now?” It was addressed at the start of the session, so it made it easier for me to focus and concentrate by having my snack when I simply felt hungry, and by the instructor making it clear that it was all right, I didn’t have any worry or anxiety around it anymore.

So imagine if this was happening in schools and the teachers are saying this to their students, then it would just eliminate any anxieties for them around, asking for what they need. It improves their focus and their concentration and therefore improve their learning and retention rate.

Another amazing thing they said was just sit comfortably. So she said, “Sometimes we might stand to do some workshops, some of them will sit down, some will be lying down” (because we had some yoga) But she said, “Whatever you need, honor your needs.” And there were some points where, again, we were stood up and she was chatting away at the end of an activity and I just needed to sit down. I just thought, “oh, getting a bit tired”, the same for my friend who’s pregnant. It sounds so simple, just sitting down when you weren’t invited to sit down, but not feeling awkward about it, not feeling rude. And it was just such a welcoming atmosphere.

And only by her saying a few words at the start of the day, it changed the whole ethos of the day, the whole vibe of it. You just felt, how do I explain it? You felt respected and I think we need to do this, we need to do this in schools.

On reflection, I just feel awful for all the years I’ve been teaching, because I’ve always insisted that my students all sit on the carpet, they all cross their legs, they all face me, and yes, it looks great. It’s easy for me to ensure that they’re all being well behaved and they’re all listening, (I presume), but actually, are they listening? I don’t really know that. If I was questioning them, obviously I do ask them some formative questions, but it’s hard to target them all, all of the time to ensure that they’re all listening. But, yeah, it’s only through having the experience of being a student for the day at this wellbeing workshop that I found that it was actually really difficult.

And no, I’m not hyperactive. In fact, I’m never really active at all. I’m pretty good at concentrating for sustained periods of time. I’m neurotypical, so I can’t quite imagine how cognitively demanding this must be for some of our learners that have these challenges anyway and naturally find this difficult.

I even had the luxury of sitting on a yoga mat, and I still couldn’t get comfortable. Every five minutes I was squirming around. And I know when children like that on the carpet in my lessons, I remind them, sit still, face the front. “Come on, cross your legs.” And it’s just not comfortable is it?

We keep asking that of our young children, children who are always really active. And it just makes me think, who are we doing this for? Is it for our benefit as the teachers? So, yeah, it’s easy for us to make sure everyone’s doing the right thing.

Or is it for compliance? Is it that notion of embedding that children should do as the adult asks them?

Is it just because we’ve been told to do that and that’s been modeled to us and our teacher training and we just follow along with it?

Or is it to ensure that we get the best learning outcomes for the students? Is it to make sure that they’re in the optimal state for listening and learning and for focusing? Is it because we put the children’s needs first and we make sure that they’re all comfortable, they all feel safe, and they all feel important and listen to?

If I was that cross legged facing the front the whole time, I’d be uncomfortable. I wouldn’t be listening properly, I’d be thinking about other things, I’d be thinking about how uncomfortable I was, how hungry I was, that I needed the toilet. And then I’d be thinking in my head, is it a good time to go to the toilet now? Has she finished speaking? Has she finished that sentence? Is she talking about the new topic? And do I have to put my hand up to go to the toilet to ask or do I just walk out now? What will people think of me when they wonder where am I going? Should I announce I’m just popping into the toilet? And you spent the time thinking about all those questions instead of just being in the present moment and learning from the instructor, like in school, instead of listening to the teacher.

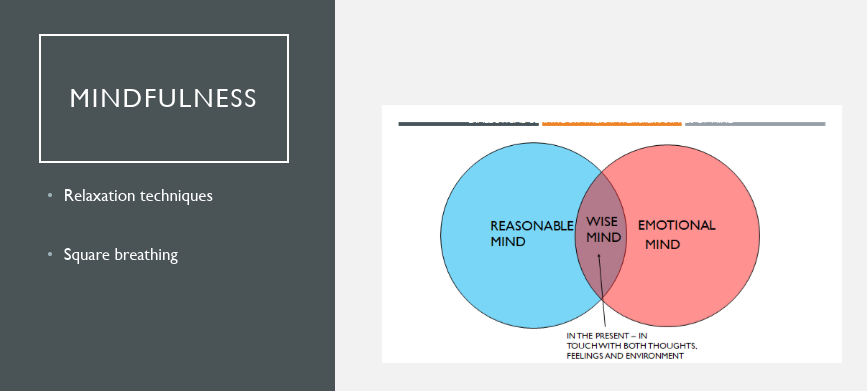

So if you’re in, say, an English lesson, the children would just switch off and be thinking those things constantly. So we just need to make this change in schools! Please, if you are a teacher, please try this out! John Swaller, who developed the cognitive load theory, says that young people can only hold between three and five pieces of information in their minds at once. That’s it – three, four or five pieces of information. Obviously, all children are different and there is a bit of leeway in that. That’s an average.

So if one of those pieces of information was the knowledge that they’re hungry, another was them thinking, “how long is it until break time when I can eat?” And the third is, “I wonder what fruit is in the snack bowl today?” And then add the hunger pangs and the frustration into the mix and there’s not much cognitive space left for learning, is there?

So if, as teachers, we told our students to put their basic needs first, such as the hunger, their thirst excretion needs, their comfort, we could free up that cognitive load for learning. And we could also eliminate all of those anxiety inducing questions that they might be mulling over and over in their heads like I was.

So let’s think about how we could practically apply these body first principles into a classroom setting.

So let’s think first about the example of going to the toilet whenever they want.

I use a signal in class, a hand signal that children can so that children can let me know when they need to go to the toilet. And they just make a T letter with their hand. So sometimes I’d use that. So they put one hand up in front of the heart vertically, and then with the other hand, they do it horizontally across the top, so it’s like a capital T in front of their chest. And then when I’m doing the instruction part, it just makes it super clear. If a child is making that T signal, I know that they need to go to the toilet. They’re not putting their hand up. So I’m not thinking,” oh, they want to ask me a random question, or they want to tell me something.”

So if I’m asking a question, say, in Maths: “tell me a number bond to 20”, and if you’ve got a hand up, I’m not thinking that they’re going to answer me, because what I often see is teachers, they’ll say, “yes, Sally, what’s your answer? You’ve got your hand up”. And when Sally says, “Can I go to the toilet?” The teachers moan, “Uhhhhh, yes, okay”. It’s an annoyance. And that’s going to cause children to feel like a burden. They’re trying to honor their needs. They need the toilet. It’s a simple human right to go to the toilet when we need to. And then this child, Sally, she’s been made to feel like she’s a burden, she’s an annoyance, and the teachers feeling frustrated with her. But that’s the rule in the class, isn’t it? Put your hand up to ask to go to the toilet. So she’s doing the right thing, but she’s not then being respected for doing that.

So if she’s making a hand signal, what I could see is, if I’m asking a question, what’s the number bond to 20? I can see that Sally has NOT got her hand up. She’s making a ‘T’ with her hands, so I know she needs the toilet. So instead of even interrupting my flow, I can make eye contact with Sally, give her a little nod or a thumbs up, then she knows she can get up and go to the toilet in silence. Nothing needs to be said between you both. And then I can go to the next person and say, “Oh, yeah, Fred, you’ve got your hand up here. What’s the answer?” The flow continues. Your lesson is not interrupted.

I do have a post on my website, actually, where I’ve made hand signals from the classroom. So there’s one for needing the toilet, there’s one for needing a tissue, one for needing a drink of water. https://cahhlmclasses.com/resources/ols/products/silent-signals-a3-digital-poster

Because we do still have those rules in most schools, don’t we, where you need to ask to do things, because if all children, all 30 children were getting up and doing whatever they wanted, it would just be chaotic. So we do still need that. Our barrier needs to be to still have to still ask for permission, but it’s without us making them feel like a burden for honoring their needs. Going to the toilet whenever we need to is one of the physiological needs in Maslow’s Hierarchy. I’m sure you’ve come across this model, but if not, it’s called Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, and it’s a model for understanding the motivations for human behaviour. And it’s a triangle shape or a pyramid, and it’s layered. At the top is self-actualization, and underneath all the layers, are the steps that you need to meet in order to reach self actualisation.

The first layer of the physiological needs are the absolute basics that we need. And in that is excretion, which we’ve covered, also in there is water and food. So let’s think about that.

So to have a drink of water in class, I think it’s pretty similar in most classes that the water bottles are kept in one particular place just to avoid spillages and work and textbooks getting wet, which I think is a fair point. And I think in most schools, we do have the rule where you ask if you need a sip of water, but you can go and get a drink whenever, really, as long as you ask in class. I say to my students that as long as I’m not teaching, (it’s not the instruction part of the lesson), then they can get up and get a drink of water whenever they need to. They don’t have to ask me. They can just get up, go to the place where we keep the water bottles. We always keep near the sink because the floor is there. There isn’t carpet, there’s just waterproof flooring. They can have a drink whenever they want, (and I say waterproof flooring – I do teach five year olds!).

But when it comes to food, what we tend to see is that children are only allowed to eat at set times. It tends to be break time in the morning where they can have a snack and then lunchtime when they serve their lunch. We also know that some children may not have breakfast in the morning.

Imagine a day when you wake up late, you’re in a rush to get ready. You don’t have time to have breakfast, and you go to a meeting or you get to school and you’ve got a fully packed morning. Your energy and concentration levels won’t be at their peak. On the days that you haven’t had breakfast, your concentration span will probably have weakened. You’ll probably be counting down the minutes until it’s break time when you can get some food. As in most schools, it’s – I wouldn’t say it’s a rule – but it’s kind of like unspoken agreement that you don’t as a teacher, you don’t sit and eat at the front of the class. You wouldn’t really eat in front of your students, especially because you have the rule that they can’t eat whenever they want to.

Now why do we really have that? I understand if we’re sat there eating unhealthy food or food that isn’t accessible to the students. It seemed as a bit unfair, isn’t it? If we’re sat there with a bag of maltesers where they can’t have anything and then a snack time, they’re only allowed apples, but what if we switched the rules up where there was a bowl of fruit, a communal bowl of fruit that was available at any time during the morning? So as a teacher OR as a student, if you hadn’t had breakfast that morning, (or even if you had it and were just extra hungry), you could just eat a piece of fruit. You probably go to an area to have your piece of fruit. So instead of counting down the minutes until it’s break time, when you can have some fruit and satiate that need, that hunger, you simply meet your need when suits you. And then this will increase your energy levels, your concentration levels, and then you’re able to then fully concentrate on your learning. And then that barrier to learning isn’t there anymore. The need has been met and that barrier has been broken down.

I suggest having the same rule for this as the drinking rule. So that as long as it’s not the instruction part of the lesson where you’re teaching and all the students are listening to you, then your pupils can get up, they can go and get their fruit whenever they need for the first week or so. I’m sure you’ll get all children wanting to have their fruit the second that they come in the door! But within a few days, that novelty factor will wear off and children will learn to identify their own hunger needs. They’ll be checking in with their body. It’s almost doing a body scan. They’ll be checking in with their hunger levels and when they notice that they are hungry, they can meet their needs then it’s giving their ownership back to them. The ownership of their needs, ownership over their body. And them being independent and recognizing when they’re hungry instead of us telling them when they should eat. It’s been recognizing this for themselves, which is life skill, isn’t it? I would also keep the rule that they can only have one piece of fruit each. So it’s not as if they get into school and they’re having a piece of fruit at 09:00 A.m. And then also having one at 10:00 A.m., and then by the time it’s break time, there’s no fruit left for anybody else. It’s that they know they have one piece of fruit. They can have that whatever time in the morning that they choose.

And the next part is allowing children to sit or stand however they want. This will help aid their concentration. Again, like the eating. So the first few days when you introduce it to the children, it is going to have a massive novelty factor and they will be a bit silly with it and they’ll be trying it on and testing your boundaries with it. But when we persist with it and that novelty factor wears off, the benefits that come from this can be enormous. The concentration will go right up.

How are you listening to this podcast? Are you sat upright? Is your back straight? Are you facing your phone like we face the front in class? And I know we do that for a sign of respect. (We’ll get on to that in a minute). You’re probably not thinking about how you might listen to a podcast best. Most people listen best when they’re doing other things – when they’re washing the pots, when they are driving to work, when they’re doing jobs around the house. It doesn’t mean that you don’t take that information in and you don’t learn from the podcasts. So maybe we should give the children the option.

So when you’re doing the instruction part of the lesson or the input, if you usually get all your class to sit on the carpet to listen to you, you could say to them, today you can choose whether you sit at the carpet or you stay sat at your desk. When they’re on the carpet, they can choose if they cross their legs or if they put their legs out straight, or even if they lie down, if they want to look at you and make eye contact, or if they want to close their eyes. Most children listen to storybooks at night time with their eyes closed and in the dark. It doesn’t mean that they’re not listening to the stories. In fact, these are probably the times that most children cherish as teenagers and adults. When we look back on our lives and we say those times when we had our stories read to us as children were in bed, they were the most magical times ever. Because of shutting off the other senses, the visual sense, which can be really distracting. It’s such an overwhelming sense. All the lights, the shades, the textures that we could be taken into our eyes. But if we shut that sense off, then it’s only going to heighten the auditory senses. It’s only going to make us concentrate more on what we can hear rather than what we can see. So therefore children will be concentrating. They’ll be paying full attention to what you’re saying.

I would give them the rule that their body language needs to be facing in your direction because if their chair was facing the opposite end of the classroom, because of how sound travels, they’re not going to hear you as clearly compared to if they were facing you. This doesn’t mean that they have to have their eyes open or their head even directly in line with yours. They could be looking down towards their table or gazing softly into space.

It is important though, to iterate that children need to be paying attention. And to check this, you could just ask them questions every now and then. Ask them simple recall questions. If they can just repeat the sentence that you last said. If they can give you the gist of what the sentence was, then yes, they’re listening and they’re paying attention. If not, then you will have to set those boundaries again and remind them of those boundaries. So they can choose to sit however they want and whatever is most comfortable for them. But they need to be paying attention to you and listening. And if they can’t do so, you might have to tighten those boundaries a bit so you might change the rules so that they’re not lying down. They can choose if they’re sitting on the carpet or at the desk.

The one point that raised in my mind about the children choosing to close their eyes or not or to not look directly at the speaker when they’re talking to them, is respect. Now, we’re taught to look into the eye of who’s talking to us as a sign of respect. And I think as long as your students can do that at a conversational level and when you just chat into them in class, if they can make eye contact with you then that’s fine to let them in lesson time close their eyes or not look at you because you know that they can do that skill. It’s maybe when the children are younger, it’s just making sure that it is also a priority that when you’re having conversations with them at play time, at dinner time, and in the lesson when they’re doing their independent work or group tasks with you, that they can make that eye contact. Making eye contact does help with making a bond with building a relationship with somebody. It helps you read facial expressions. You can tell by the way that their eyes move, for example, if they’re squinting, it will help you understand if they’re smiling or frowning and it can improve the understanding between each of you.

So to summarize our episode, we’ve talked about how we can introduce the ‘Body First’ approach into our classrooms by putting our students needs first – so their needs, such as thirst, hunger, excretion & comfort. And we can give our students the authority to put their own needs first by altering our classroom rules and introducing hand signals so that the children can communicate their needs to us.

Because these basic physiological needs, according to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, are our absolute basic human needs. And until those basic needs are met, they act as huge blockages that prevent our students from learning. So, (like we spoke about in episode one, ‘The Only Things That Cause Challenging Behaviour in Children’), when students have an unmet need – so if they’re hungry or if they need the toilet – the body is constantly sending them signals to say, “Help me! Help, I need something!” And until that needs met, the body is going to keep sending those signals. And these signals are distractions to the children (and to adults as well). These signals and distractions won’t stop until that needs met.

I’m thinking of the cognitive load theory that John Sweller developed. And when our brain’s cognitively overloaded, the learning process either slows right down or completely shuts. It completely stops because the brain can no longer process all the information. And that means that the children aren’t learning, and they’re not going to remember what you’re saying. So we need to meet those needs in order for them to learn.

The body first approach isn’t just for the neurodiverse learners, but also for the physically diverse. It’s for all our learners. We’re also unique in so many ways, and we all have needs. This is a way to make sure that our children come first. And as our educators, we adapt the learning environment to be as suitable for learning as we possibly can. We spend years teaching the children to sit still, and is this for our benefit or for theirs? No wonder it takes them years to learn. It’s against our very nature. As human beings, our bodies are designed to be active, to support our circulation. So when we spend years insisting that they sit still, and then when they’re teenagers and they’ve eventually mastered it, society’s then telling them to not be sedentary and to move more. So maybe we should think about changing our classroom expectations so that they suit the children instead of suiting us adults? We should put the children first and meet their needs instead of fighting against that grain and causing us all frustration and annoyance. When children can’t sit still and they can’t listen perfectly, we meet them where they’re at and we do what’s best for them.

Thank you for spending time with me today, and I’d love to hear if you implement these ideas in your classroom. Let me know how you get on.

Speak soon!

Holly Morris

Cognitive Load Theory – https://researchschool.org.uk/durrington/news/cognitive-load-theory-and-what-it-means-for-classroom-teachers